Synopsis

Any attempt to proclaim a single masterpiece of any genre, from opera or symphony to rock song or jazz concert, as the greatest, the most influential or even the most enjoyable is properly dismissed as utterly meaningless. Yet when it comes to ballet music, all three superlatives tend to coalesce around one work above all others – Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 1876 Swan Lake.

It seems futile to offer a definitive abstract of Swan Lake, as most stage presentations reflect sweeping departures from the original conception. Indeed the synopsis published with the full score differs, often fundamentally, from those provided with many recordings. Moreover, as a general matter, the intrinsic nature of the art of dance unavoidably eludes precise narrative in favor of abstract pantomime, regardless of the librettists’ intentions. Thus ballet faces an immediate hurdle when compared to the narrative devices used in other primarily visual performing arts, as it is unable to specify meaning by relying upon and benefiting from the specificity of lyrics (opera), dialog (movies, plays, operetta, shows) or titles and inserts (silent film). Indeed (at least to me), much of the detailed action of Swan lake is hard to infer from numerous videos of prominent performances.

Let’s place the story in context. John Martin observes that the accepted practice of the time was to use the plot of a ballet as a mere thread upon which to hang a succession of divertissements regardless of their appropriateness to the theme. Swan Lake was no exception – each act but the last includes extensive danced entertainment that has little to do with the plot and often interrupts it. Many of the most popular ballets (Coppelia, Cinderella, The Firebird, Don Quixote) present serious themes but end with lavish celebrations – even Tchaikovsky’s own Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty devote their entire final acts to extensive joyous fêtes. In a sense, though, the bare stories of ballets hardly matter – as James Lyons notes, they tend to be embarrassingly trite when reduced to cold type. Rather, “in the theatre they are told on quite another level of discourse. From behind the footlights their logic is unassailable, their sentimentality becomes sentiment … and no heart can be unmoved.”

With that in mind, here is an abbreviated amalgam to relate the 29 numbers in the original score to the basic stage action. (Please click here for a more detailed structural outline that may be more helpful in following the references to the numbers (and for several, their subparts) that are used throughout this article.) Before the curtain rises an introduction sets a mood of anticipation and foreboding and which we’ll refer to as # 0.

Act I – The Garden Outside Prince Siegfried’s Palace

While celebrating Prince Siegfried’s coming of age with local well-wishers (1: Scene), his elderly tutor Wolfgang invites villagers to dance (2: Waltz). Siegfried’s disapproving mother enters and commands that he is to select a bride at a ball the following evening (3: Scene). After she departs, the peasants try to cheer him up (4: Pas de trois; 5: Pas de deux). Now inebriated, Wolfgang dances awkwardly and collapses (6: Pas d’action). Further dancing (7: Subject; 8: Dance with Goblets) fails to dispel Siegfried’s gloom. As the others depart, his friend Benno urges him to come on a swan hunt (9: Finale).

ACT II – That Night – A Lakeside In The Mountains

Swans glide across the lake and disappear from sight (10: Scene). As the hunters approach, a beautiful girl appears, dressed in white and wearing a crown. She explains that she is the Princess Odette, under a spell cast by the evil sorcerer Von Rothbart that binds her and her companions to be swans by day and humans at night and that can only be broken by a vow of eternal love. In the guise of an owl, Rothbart threatens Siegfried. Enamored of Odette, Siegfried tosses aside his weapon, confesses his love and invites Odette to the ball (11 and 12: Scenes). Transformed into maidens, the swans return and a variety of dazzling dances ensue for the entire ensemble, smaller groups, Siegfried and Odette as solos and then together (13: Dances of the Swans). Odette promises to attend the ball, but as dawn nears she tears herself away to join the other maidens who reappear on the lake as swans (14: Scene).

ACT III – The Next Night – The Palace Ballroom

The court and retinue enter (15: Introduction and Dance of the Fiancées). Foreign guests pay their respects (16: Dance of the Corps de Ballet and Dwarfs). Six eligible princesses are announced and each dances for, and briefly with, Siegfried, who cannot choose among them (17: Fanfares and Waltz). Rothbart enters with his daughter Odile, who is dressed as a black swan and is disguised as Odette. [The same ballerina usually dances both roles.] Deceived, Siegfried welcomes her (18: Scene). Foreign guests present their native dances as entertainment (19: Pas de six; 20: Czardas [Hungarian Dance]; 21: Bolero [Spanish Dance]; 22: Neapolitan Dance; 22a: Russian Dance; 23: Mazurka [Polish dance]). Odile seduces Siegfried who swears eternal fidelity and, to his mother’s delight, announces he will marry Odile, as Odette looks on helplessly through a window. As thunder crashes, Rothbart and Odile reveal their treachery to the horror-stricken court and gloat as Siegfried rushes out (24: Scene).

ACT IV – The Lakeside

The swans await Odette’s return (25: Entr’acte; 26: Scene; 27: Dances of the Little Swans). She tells them of her betrayal (28: Scene). At this point, the treatments differ radically (29: Final Scene). In the original libretto Siegfried begs Odette’s forgiveness, which she is powerless to grant, he exclaims that they must remain together forever, she dies in his arms, he drowns himself in the lake, and the other swans glide by once more. In most other, more sanguine, versions once the lovers kill themselves Rothbart’s evil power is nullified, the other swans are released from his spell and the spirits of Odette and Siegfried ascend to eternal heavenly happiness (although, as George Balanchine points out, the tragic tone of the concluding music abrades a happy apotheosis). There are many variants: Siegfried kills Rothbart, breaking his spell, Odette becomes human and the lovers survive united; Odette remains a swan as Siegfried grieves alone; Rothbart kills Siegfried, leaving Odette alone; Siegfried throws Rothbart over a cliff, breaking his spell; the swans kill Rothbart, enabling the lovers to live on as mortals; or Siegfried’s mere willingness to die for Odette is sufficient to break the spell and they live happily ever after.

While it’s tempting to sneer at the revised endings, let’s recognize that the original conception of Swan Lake fundamentally is a fairy tale with all the traditional elements save one. It’s full of magical transformations, lurking evil, gallant protagonists, exotic diversions, forces of nature and a mythical setting. All it lacks is the requisite happy ending of just rewards in which evil is thwarted, the social order is restored and the lovers live happily ever after. Rather, at least as originally conceived, Rothbart triumphs, the lovers are dead and the enslaved swan maidens return to their dismal future of endless misery. So who’s to blame all the subsequent producers for delivering a more gratifying outcome?

Ballet Before Tchaikovsky

The urge to bodily expression is prehistoric, may predate language and is assumed to have played a major role in ancient religious ritual. The depth and pervasiveness of its cultural roots is evident from the frequent references to dance in the Bible and its frequent depiction in images ranging from the Parthenon friezes to the Hindu god Shiva balanced on one leg.

Formalized ballet as we know it can be traced to the sumptuous royal entertainment of Elizabethan masques and Louis XIV, an ardent and accomplished enthusiast, in whose court the nobility performed strict dance routines to exhibit the grace and dignity of their high culture (and, undoubtedly, to distinguish themselves from the raucous, lusty dancing of the peasantry). By the baroque era, the dances themselves assumed an integral part of serious abstract music (as in the Bach Suites) and played a major role in symphonies both classical (as minuets) and romantic (scherzos). Moving to the stage and performed by professional artists, by the mid-1800s ballet had become such an integral facet of Parisian culture that it was an obligatory part of operas presented there, whether logically integrated into the plot (as the BallibiliVerdi was compelled to insert into the third act of his Otello to precede the grand entrance of Venetian ambassadors) or not (the lovely but incongruous “Dance of the Hours” in the midst of the Inquisition in Ponchielli’s La Gioconda). Indeed, the ballet sections of many 19th century operas achieved fame independent of their source (Rossini’s William Tell; Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld; Massenet’s Le Cid). As a measure of the popularity but lesser status of 19th century ballets, they often were performed as part of a lengthy program following a complete opera.

The earliest full ballet remaining in the repertory is the hour-long 1832 La Sylphide which, in a harbinger of the plot of Swan Lake, finds a Scotsman fatally lured through witchcraft from his bride-to-be by an enchanting woodland nymph. But don’t rush out to buy a CD of the music (by Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer) – it appears to have never been recorded (other than as the soundtrack to videos of performances) and with good reason – while functional and rather effective in context to support the narrative, it’s utterly forgettable. Much the same can be said of other pre-Tchaikovsky ballets that remain popular – the music of Don Quixote (by Ludwig Minkus) is rarely heard and the scores of Giselle (Adolphe Adam, 1844) and Coppélia(Léo Delibes, 1870) are full of filler and best heard in suites that can focus on the few memorable melodic portions (the brisk waltz and Act I pas de deux of Giselle; the stirring mazurka and beguiling thème slave varié of Coppélia). Perhaps the ultimate test of a ballet score (or a film soundtrack, for that matter) as pure music is whether it can sustain interest in a concert hall or as an audio-only recording; until Tchaikovsky, none could.

A related measure is to consider the numbers of audio recordings – as of 2000, when one of the last Schwann catalogs appeared, not only La Sylphide but Don Quixote and Minkus’s La Bayadère had none at all, while Giselle, Coppélia and Delibes’s Sylvia had a mere two each (plus 3, 8 and 6, respectively, of their suites). Compare Tchaikovsky – the same catalog lists 16 records of his complete Nutcracker (plus another 37 of the Nutcracker Suite), 6 of Sleeping Beauty (plus 32 of its suite) and 6 of Swan Lake (plus 34 of selections).

To be fair, James Lyons asserts that great ballet music does not have to be great music, as dance is the most ephemeral of the arts, a thing of the moment (and memory). And, as Lincoln Kirsten observes, ballet music has intrinsic limitations – while it serves as the root rhythmic base that impels movement while ordering and emphasizing the activity on stage, it should not compete with the action, much less dominate it. Yet Tchaikovsky’s impact upon the accepted subsidiary role of ballet music was huge, as the genre soon would emerge in its own right as worthy of sustained intrinsic interest, to be heard more often on record and in concert than as ballet accompaniment: Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun and Jeux, Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé, Stravinsky’s Firebird, Petroushka and Rite of Spring, Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet and Cinderella, Copland’s Appalachian Spring. (The beloved score of the 1909 Les Sylphides – not to be confused with the 1832 Schneitzhoeffer La Sylphide– can’t count as an original composition, as it comprises orchestrations of gorgeous Chopin piano pieces.)

In the mid-19th century an influx of imported talent had shifted the focus of ballet to the wealth of czarist Russia, but in the view of several scholars the artistic level soon sank. As Peggy Cochrane put it: “Costumes and settings were tasteless and lacking in distinction, music was insipid and flavorless, and dancers indulged in vulgar displays of meaningless technical virtuosity.” As for the music, one commentator described it as “a not very inspiring series of set pieces, largely to a fixed pattern, containing harmonic clichés and melodic trivialities that could barely stand on their own for concert purposes.” Alfred Leonard points out that no important composer had written for the ballet since Beethoven’s 1801 Creatures of Prometheus (which in any event hardly ranks among his greatest achievements).

Emergence

While on vacation in 1871 Tchaikovsky had created for his sister’s children a family entertainment involving swans on a lake. In 1875, Vladimir Begichev, a friend with whom Tchaikovsky had travelled throughout Europe, and who had become the director of the Russian Imperial Theater in Moscow (of which the Bolshoi was the crown jewel), commissioned a score for a libretto he had fashioned, possibly in collaboration with Vasily Geltser, the ballet-master of the Bolshoi and Julius Reisinger, its resident choreographer. Tchaikovsky wrote that he accepted the commission for Swan Lake “partly because I needed the money and partly because I have long cherished a desire to try my hand at this type of music.” He studied the scores of prior ballets, admired Giselle for its romantic, supernatural plot (in which ghostly spirits of betrayed maidens avenge their newest member by forcing her lovers to dance until fatally exhausted), and at first considered an adaptation of Cinderella. The story of Swan Lake was intriguing, as it was rooted in ancient myths of swans as a symbol of womanhood and legends of women transformed into birds.

But Tchaikovsky also might have been enticed by its derivation from operas in which men fell in love with enchanted women, a situation eerily resonant with his own bizarre personal history, in which he foreswore marital life for a chaste but deeply passionate relationship, conducted entirely through correspondence, with a wealthy widow. He sketched the entire score that summer and, amid other work, completed the orchestration by April 1876.

The original score is no longer extant, and scholars largely have been unable to recreate the premiere performance, forcing reliance upon inferences from surviving artifacts. Yet it seems clear that the debut was a severe disappointment due to a confluence of problems. The conductor was an amateur, ill-equipped to handle the challenges of the score. Anatole Chujoy considers the choreographer Reisinger “a hack with no talent or taste for the task” and the prima ballerina, Pauline Karpakova, a “run-of-the-mill dancer past her prime.” Worse, as the gala was to have been a testimonial in her honor, Karpakova was unwilling to risk any chances and insisted upon interpolating sure-fire numbers from her repertoire. Critics were brutal, focusing on monotonous and unimaginative choreography. One cited the “incoherent waving of arms and legs [that] continued for the course of four hours” as torture. “The corps de ballet stomp up and down in the same place, waving their arms like windmills’ vanes and the soloists jump about the stage in gymnastic leaps.” Protested another: “I have never seen a poorer presentation on the stage of the Bolshoi.” The prompt replacement of Karpakova with Anna Sobeshchanskaya, for whom the role had been intended, and new choreography by Olaf Hansen in 1880 and 1882, had no better impact.

Yet those same critics approved the music, even though they might not have realized that substantial portions were thought undanceable and had been cut in favor of Karpakova’s substitutions – plus, as James Lyons notes, in light of the depressing action on stage, the audience might have been too upset by what it saw to be much aware of what it heard.

While the practice of the time was for a composer to closely tailor a ballet score to a detailed scenario (as Tchaikovsky would do for his Sleeping Beauty and Nutcracker), in this instance he had little direct guidance from the authors and was left largely to his imagination. As a result, the music was structured in broad gestures and treated rather abstractly. Ann Nugent feels that the company couldn’t relate to music that went beyond mere accompaniment and support but rather asserted itself with melodic and psychological development.

Even so, Tchaikovsky blamed himself for the failure. Charles Reid characterized him as “an introspective young genius with a talent for psychological self-torture. … As was invariably his way, when anything went wrong, Tchaikovsky blamed himself.” After hearing Delibes’s contemporaneous Sylvia (notwithstanding its stale plot, in which the titular huntress’s love for a shepherd is abetted by Eros), he dismissed his own score as trash and wrote: “If I had known this music earlier I wouldn’t have written Swan Lake, for it is poor stuff compared to Sylvia,” a judgment awfully hard to sustain nowadays. Indeed Tchaikovsky had so little self-confidence that he consented to write another ballet, Sleeping Beauty, only if he was promised exhaustive guidance in the form of minute details of the required numbers. As for Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky intended to rewrite the score but never did. As Charles Reid asserts: “Happily for posterity he never found the time to do this. One cannot imagine the music bettered.”

While the Swan Lake premiere engagement is often cited as a failure, several historians note that it remained in the Bolshoi repertoire for six years, longer than a typical run of the time. Nikolay Kashkin (who made the first piano transcription of the score) recalled that it was retired only when “the scenery wore out and the décor became ragged.” Even so, Tchaikovsky witnessed only a single further performance, and only a partial one at that, when he led Act II in Prague in 1888, after which he wrote that it had been a rare moment of blissful happiness. When he died in 1893 it was assumed that the dim flame of Swan Lake had flickered briefly and would remain forever extinguished.

Triumph

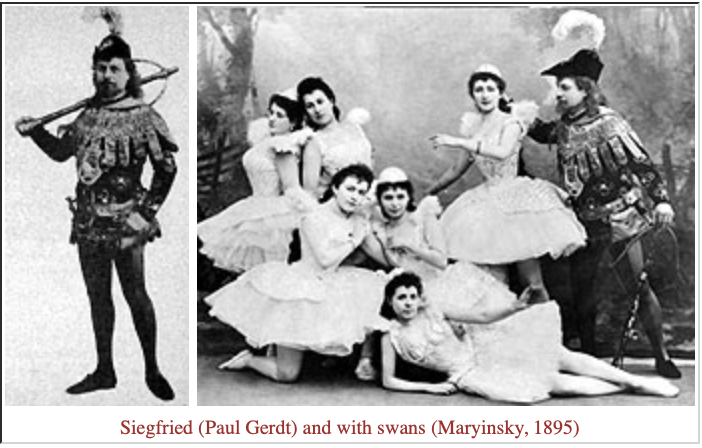

That soon would drastically change. Act II was included in a February 1894 memorial program, freshly choreographed by Lev Ivanov and brilliantly danced by the acclaimed Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani. It attracted great interest – one critic raved: “What continuity, what plasticity, what velvety-soft movements, what tenderness and execution!” Further prompted by the success of Tchaikovsky’s two subsequent ballets, Sleeping Beauty (1890) and The Nutcracker (1892), the Maryinski Theater in St. Petersburg, arguably the foremost ballet venue in the world at the time, undertook a revival of the full work.

Marius Petipa, its ballet master, had worked with Tchaikovsky on Sleeping Beautyand The Nutcracker, admired the music and blamed the Moscow experience on poor production.

Unfortunately, the product that emerged, while reviving Swan Lake’s fortunes, was far removed from Tchaikovsky’s original, as his brother Modeste revised the scenario and the conductor Riccardo Drigo substantially reorchestrated it, rearranged the order of the pieces (to a sequence that is still commonly used) and inserted orchestrations of three solo piano pieces from Tchaikovsky’s 18 Morceaux, Op. 72. (The mutilation process actually began with Tchaikovsky’s himself even before the Moscow premiere when he accommodated Karpakova’s demand for a pas de deux display piece (comprising a leisurely introduction, a brief waltz, a quick scurry and a vigorous coda which became designated as # 19a in the score) and Sobeshchanskaya’s wish for a Russian Dance (which became # 20a). Following the composer’s own acquiescence, cuts and substitutions throughout the rest of the original run became commonplace, so that by its end barely 2/3 of the score remained intact.)

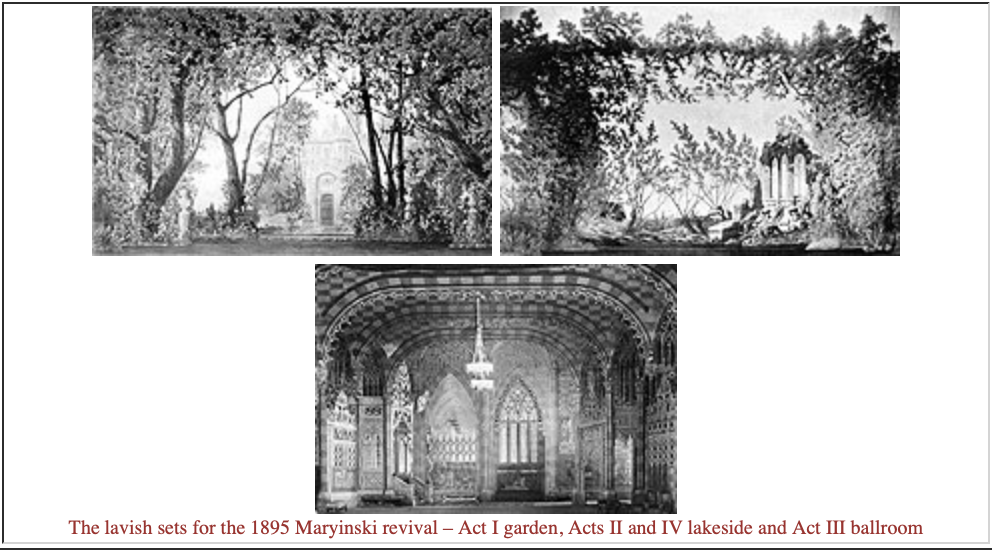

Musical integrity aside, the Maryinsky revival was a huge success, due in no small part to the masterful choreography. As traced by Carol Lee, Petipa had a broad background to prepare for his key role – he had been trained in music, absorbed the colorful rhythms and steps of Spain, served as premier danseur in St. Petersburg, and developed a gift for diplomacy to assuage the egos of his artists. Lee credits him with emphasizing abstraction over story-telling and expression over pantomime, while synthesizing superb physical skill with sumptuous spectacle, an approach that pleased audiences without compromising artistic integrity. While tailoring solos to his artists’ particular qualities, he crafted exquisite kaleidoscopic patterns for his highly-trained corps de ballet (the dancers who perform together rather than solo) and won their loyalty with lifelong pensions. Even so, he choreographed only the first and third acts of Swan Lake, entrusting the rest to his equally brilliant assistant Ivanov who is credited with taking inspiration from the score itself to create new movements and patterns as organic extensions of the musical principles. Anderson hails the resulting duality of drama reflected in the different choreographic styles – the sharp clarity of the colorful indoor pageantry of Petipa’s Acts I and III alternating with the nature-infused lyricism of Ivanov’s Acts II and IV.

Chugoy gives as a primary example of Ivanov’s innovation his integration of forces – rather than soloists performing on a bare stage or against an immobile group of dancers, Ivanov had them all interact as a sort of grand duet. Indeed, this seems analogous to the way in which a musical melody line blends and interacts with its harmony, so that the dancing operates on a level parallel to the score. Anderson further salutes ever-changing patterns of the corps de ballet that emphasize the lines and shapes of the soloists, while their steps evoke the very nature of swans’ preening and striving for flight and freedom. That, in turn seems a precursor of modern ballet in which leading ballerinas are dethroned as the raison d’etre so as to become just one of the protagonists who participates with the others. But esthetic history aside, by several accounts the success of the revival was incited by Legnani who created a “must-see” sensation by performing toward the end of Act III a series of 32 consecutive fouettés (whipping out her free leg during a quick turn), a feat of stamina that is preserved in most modern choreography and that has since challenged nearly every ballerina in the role.

Sarah Kaufman notes that, without a reliable record of the original intention, Swan Lake necessarily is an evolving work of art, and indeed its greatest strength lies in forcing successive artists to offer new insights tailored to their times and colleagues.

Ballanchine agrees that the very notion of a permanent record of a ballet became technologically possible only long after Swan Lake’screation and that in any event it is entirely proper for a living work of art to reflect the proclivities of each generation of the public and the artists upon whom they depend. Even so, most further productions were mere abridgements or isolated acts, as the first full presentations reached England only in 1934 and the US in 1940. While most are traditional, perhaps the most drastic adaptation is by South African Dada Masilo; according to reviews and press releases, “retooling the narrative to address issues of societal pressure, segregation and homophobia,” it features a gay Siegfried, barefoot men in tutus and traditional African dances.

Many commentators now rank Swan Lake as the most popular of all ballets (although the sheer ubiquity of the Nutcracker, which few ballet companies can resist mounting to replenish their coffers each winter holiday season, clearly has come to supersede it in the public eye). Indeed, no other composer has placed three ballets in the standard repertoire (and only Minkus, Delibes and Prokofiev can boast two), much less at the very top. The reasons given are many: its romantic theme of impossible love (Anderson), a heroine who is entirely a creature of the imagination, at home in sea and sky but utterly lost in the real world with no control over her destiny, which ennobles her beauty (Ballanchine), a leading role that manages to be not only brilliant and varied technically but sad, sweet and romantic (Martin), and representing the ultimate embodiment of Romantic extremes – Odette is the vision of purity, nobility and poetry while her Odile form is corrupt, sinister and destructive – which presents the ultimate challenge to a ballerina as dancer and actress (John Gruen). Leo Lerman asserts that after the 1895 revival “every reigning ballerina measured her importance by the success of her Odette-Odile and every premier danseur did not believe himself established until he had partnered her.” Anderson adds that the swan costume of tutu (possibly derived from the outfit worn by the sylphs in La Sylphide) and headdress have become the very symbol of a ballerina, and that the 32 fouettés launched by Legnani remain ballet’s most famous display of virtuosity.

The Music

It’s a bitter shame that Tchaikovsky never lived to enjoy Swan Lake’scolossal success. Indeed his score has come to be universally lauded, despite others’ constant attempts to “improve” it. Rather curiously, Tchaikovsky’s symphonies, and especially the Fourth, were faulted in their time for containing ballet music (although ironically, as Alexander Demidov notes, that very factor made them accessible to the public). Yet as Reid stated: “The notion that theatre and concert room are watertight compartments is fusty nonsense.

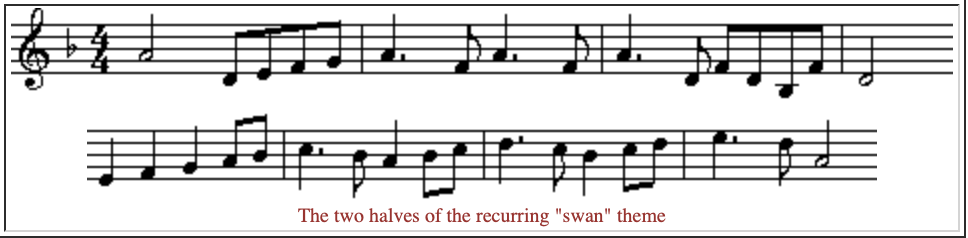

The symphonic craft that Tchaikovsky brought to the theatre was as revitalizing as the touch of theatre that he brought to symphony writing.” Indeed, the foremost quality most often attributed to the Swan Lake score nowadays is its “symphonic” nature, an innovation for the genre (albeit somewhat inspired by Delibes), although early critics stigmatized it as undanceable for that very reason. (Clearly they used the term rather loosely, as the score hardly resembles the structures and thematic development of a genuine symphony.) More recent analyses point to the then-revolutionary use in a ballet score of recurrent leitmotifs (primarily the “swan theme” that appears in manifold guises) to signify character and to unify the entire work, together with a wide variety of textures and colorful orchestration to underline mood and sustain interest throughout a long evening. Indeed, Harold Schonberg deems Tchaikovsky’s ballets to be close to opera, with the equivalent of arias, duets and ensembles scored for dancers rather than voices. Gruen praises its scope, as it “captures like no other the full range of human emotions from hope to despair, from terror to tenderness, from melancholy to ecstasy.” Indeed, the moods extend from the exquisitely tender violin solo of the Swan Dance Andante (# 13e) to the thundering explosions of the finale (# 29), with an abundance of colorful variegated numbers in between. André Tubeuf salutes the emotional complexity of the score, contending that Tchaikovsky could not help but to inject into the fairy tale his own tragic tension: the burden of a crime [presumably a reference to his homosexuality] that, in the manner of Dostoyevsky, he felt he was carrying, resulting in an undercurrent of sorrow, poignancy and grief that is all too often hidden on the stage by superficial dancing and on records by the hedonism of conductors.

But much of that level of analysis is rather subtle, especially when audiences are properly focused on the stage. Far more palpable is the profusion of magnificent melodies that Tchaikovsky lavished on Swan Lake. The tunes comprising earlier ballet scores serve their immediate purpose well enough but float in one proverbial ear and out the other. Tchaikovsky’s are unforgettable. Yet their charm and resilience occasionally prompts censure as shallow, prompting Reid to note that the bulky miniature score is a handy size “for throwing at the heads of critics who are lofty about Tchaikovsky because the milkman and butcherboy have been known to whistle him.” Reid further hails the array of national dances in Swan Lake as reminders of Tchaikovsky’s creativity, as he could smoothly assume any alien idiom and adapt it to the needs of a given work. In that light, Lee considers the striking variety of the tunes as exemplifying Tchaikovsky’s cosmopolitan gift of combining Western and Slavic musical traditions, thus uniting the dichotomy of the two camps that divided Russian composers and theoreticians at the time. Yet, unlike in The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky doesn’t clump the best tunes together back-to-back in an unbroken block of entertainment but spreads them throughout the score (until the final act, which focuses on the dénouement). Nor, unlike in The Nutcracker, does Tchaikovsky ever resort to stylized natural sound (the tolling clock, the percussive battle) or a wordless chorus to underline his purely instrumental musical conceptions.

A further irony is that, as so often in art, Tchaikovsky’s innovations impeded initial acceptance and success. In that regard, Demidov notes that Tchaikovsky’s new (to ballet) principles of organization required innovative thinking that challenges choreographers to realize – and that at first they failed to penetrate the world of his musical-psychological drama. And yet, it would seem that by including the sections of sheer entertainment and diversion that had nothing to do with the story but were dances for their own sake, Tchaikovsky invested Swan Lake with enough traditional elements that should have ensured its immediate acceptance. In the longer view of history Goodwin concludes that, by treating ballet as a subject worthy of musical imagination, Tchaikovsky not only achieved an enduring masterwork but set a new standard for the role of music in ballet.

Suites and Selections

So many of us came to love The Nutcracker (and perhaps classical music in general) through the ubiquitous Nutcracker Suite, comprising that ballet’s Overture miniature, six distinctive “characteristic” dances and the Waltz of the Flowers – an authentic compilation arranged and conducted by Tchaikovsky himself to promote his new ballet preceding its premiere; indeed, the score of the suite was published seven months before the ballet was first performed. Yet despite what might be assumed from the titles of numerous recordings there is no comparable “official” compilation for Swan Lake. In 1882 Tchaikovsky had written to his publisher Peter Jurgenson that he wanted to save Swan Lake “from oblivion since it contains some fine things” and requested a copy of the complete piano score (the only version published at the time) to specify which numbers to include and their order. But he never mentioned it again and the project never materialized. Rather, in 1900 Jurgenson published a suite of unknown provenance consisting of six sections of the ballet.

While many recordings follow Jurgenson’s sequence of numbers 10, 2, 13d, 13e, 20 and 29, many others regard this as a mere springboard to be augmented with other portions or even for wholesale departures in favor of their own choices. (The suite from Sleeping Beautylies between the authenticity of the Nutcracker Suite and the uncertain origin of the Swan Lake suite – after the ballet was introduced Tchaikovsky sensed public interest but was afraid that, as an author, he “invariably makes mistakes in the appraisal of his creations” and couldn’t choose excerpts “because the whole ballet is of equal merit,” and so he entrusted the project to Aleksandr Ziloti, a distant relative and close associate. Following Tchaikovsky’s wishes, Ziloti’s suite comprised discrete numbers including the famous waltz from Act I rather than a potpourri but it only appeared posthumously in 1899, perhaps paving the way for Jorgenson’s Swan Lake suite the next year.)

Prior to the release of full recordings, the music of Swan Lake emerged gradually on disc over a half-century in a disparate array of excerpts. The earliest ones I’ve encountered are abridgements of three dances (#s 2, 13 and 20) by the Coldstream Guards, a British regimental band that boasts an extraordinary history from 1785 to the present including a superb series of releases from the dawn of acoustical recording. As with all their early discs, these boast tight ensemble and stirring articulation and still sound thrilling – if you don’t mind flatulent tubas puffing away, as was customary to avoid the distortion caused by string basses in the acoustical process. The first set of extended excerpts appears to have been of the first five numbers of the suite played with enormous rhythmic heft by the London Philharmonic led with vast excitement by John Barbirolli, concluding with a manically fast “Hungarian Dance” (perhaps to fit onto four generously-filled 12″ sides). According to various reference works, other 78 sets followed from Dorati/London Philharmonic (8 sides, Columbia, 1938), Beer/National Symphony (4 sides, Decca, 1945), Golschmann/St. Louis (10 sides, Victor, 1945), Rignold/Covent Garden (4 sides, HMV, 1948), Kostelanetz/”His Orchestra” (10 sides, American Columbia, 1950) and a remake by Barbirolli/Hallé (4 sides, HMV, 1951). The LP era accelerated the pace, bringing annual releases from Karajan/Philharmonia (Columbia, 1952), Irving/Philharmonia (RCA, 1953), Rodzinsky/Vienna Symphony (Westminster, 1954), Lehmann/Bamberg (1955), Ormandy/Philadelphia (Columbia, 1956), Sawallich/Philharmonia (EMI, 1957) and Fricsay/Berlin Radio (DG, 1957). The analysis compiled by The World’s Encyclopedia of Recorded Music (WERM) documents that some follow the Jurgenson Suitewhile others present a striking variety of other or additional numbers.

In the listings below, the numbers correspond to those in the full orchestral score, as designated in the attached outline. While most provide a fine introduction, five are of especial interest, as they presumably benefit from the insights provided by their conductors’ extensive backgrounds in ballet.

Antal Dorati, London Philharmonic – (Columbia, 1938)

Although he primarily would be famed for his pioneering and idiomatic Haydn recordings (including the first complete stereo set of the symphonies and revivals of a dozen forgotten operas), Dorati devoted much of his early career to leading the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the American Ballet Theatre. Thus it seems rather surprising that while the overall pacing of his Swan Lakeset is more moderate than Barbirolli, many tempos still seem quite fast for dancing, and while the pulse is mostly steady he floors the accelerator at the end of several pieces and draws out the notes at the end of each clause of the mazurka (# 23) – a nice touch for listening but seemingly confusing in the context of a stage presentation. Presumably to accommodate the side length limitation several numbers are abridged. Although the order of the pieces is scrambled, the groupings on the third and fifth sides fit well together (and transitions between the other sides are irrelevant, as they were not intended to be heard in rapid succession as on modern transfers, since the requirement of changing discs at the time provided built-in pauses). Even so, the selection is unusual, omitting several favorite portions: the haunting swan theme (other than in its strained form in the finale (# 29)), the Act I waltz (# 2), the Hungarian dance (# 20) and the gentle apotheosis that concludes the finale, which here ends abruptly with a tacked-on symphonic cadence.

Roger Désormière, French National Radio Orchestra – (Capitol, 1951)

Désormière, too, launched his career in ballet, in his case leading the final four years of the original Ballets Russes (to which the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, with which Dorati was associated, was a successor) under Serge Diaghilev, one of the most influential and revolutionary choreographers of all time.

The uncredited notes to this album commend Diaghilev with creating what is now considered the standard version of Swan Lake for his company’s 1911 production and goes on to attribute to the tempos and phrasings of this recording the authenticity and authority of that tradition. That’s hard to confirm, but what can be said is that Désormière leads a thoroughly persuasive reading that is graceful and elegant – not a tone poem but a soundtrack for ballet, with a sure regard for its purpose. Thus, while others feel compelled to goose the Act III characteristic dances to wild conclusions, here they accelerate gently and moderately, prudently tempering a yearning for exhilaration with keeping the spotlight on the dancers. While the notes by André Tubeuf to the EMI References LP reissue ascribe an “etching-like quality,” I disagree – rather than the sharply-defined, monochromatic rigidity suggested by that term, this reading emerges as colorful and natural, building organically and displaying well-balanced instrumental voices – and by doing so underlines the brilliance of Tchaikovsky’s achievement that manages to function superbly in two seemingly conflicting roles, both as a ballet score and as pure music. The fidelity, though, is disappointingly dull and thick for its time.

Robert Irving, Philharmonia – (HMV, 1953)

Unlike the other conductors in this group who developed a solid foundation in ballet but then went on to more diversified and presumably more rewarding careers before inscribing their Swan Lake collections, Irving devoted his entire professional life to ballet – a decade with the Sadler Wells company and then an astounding 30 years with the New York City Ballet. There, he worked closely with luminaries who were elated with his collaboration: Martha Graham averred that he “knew how to get the music under the dancers’ feet,” George Balanchine said, “With our orchestra if you don’t like what you see you can close your eyes and still hear a good concert,” and New York Times senior music critic Harold Schonberg pronounced him “possibly today’s foremost conductor of ballet.” With those encomia and few distractions from other musical fields, Irving provides an exemplary set of Swan Lake excerpts, with fine rhythmic sparkle yet moderated with exceptionally smooth transitions. Although the sound is somewhat more incisive, Irving’s spirit is comparable to Désormière’s. Yet he resists the temptation to scramble the chronology and presents the pieces strictly in their order on stage. (The shift of parts of the Act I pas de deux (# 5) to Act III as a duet for Siegfried and the Black Swan [in lieu of the piece Tchaikovsky had added for Karpakova] was common at the time.) Also unusual among severe abridgements is the intact presentation of nearly the entire final act, which, while accompanying the most essential part of the narrative, has the least appealing part of the music. In contrast to the 45 minutes or so typified by the Désormière LP, Irving’s generously fills the two sides with 55 minutes of music.

Efrem Kurtz, Philharmonia – (Capitol, 1958)

Following in Dorati’s professional footsteps, Kurtz served as the conductor of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo for a decade. Before that, he had accompanied the famed dancer Anna Pavlova for three years. Lest we forget that music marketing is a business, presumably to boost its sales appeal the LP cover gave prime billing to the relatively brief appearances of Yehudi Menuhin, Kurtz’s far more famous guest soloist, in two of the most touching numbers – the Andante of the pas de deux (# 5b) and the Pas d’action section of the Dances of the Swans (# 13e). Perhaps to expand Menuhin’s role and warrant his publicity, Kurtz concludes with the rarely-heard Russian Dance which Tchaikovsky added to the score to accommodate Sobeshchanskaya and which features a lengthy slow introduction with characteristic Slavic fiddling that affords a more varied opportunity for solo display than the two other pieces. Like Irving’s, the Kurtz sequence is a generous 54 minutes and follows the order in the score (with the pas de deux restored to Act I) yet omits all of Act IV and includes more of the tuneful dances rather than the narrative/transitional episodes. His tempos tend toward extremes more than his peers’, raising intriguing speculation as to whether this is an accurate representation of how he led pit orchestras during actual stagings or an accommodation to the impact of a record that relies entirely upon audio stimulation.

Pierre Monteux, London Symphony – (Philips, 1962)

Of all the conductors with roots in ballet, Monteux was the most famous, and deservedly so. At the Ballets Russes during its most exciting and influential era from 1911 through 1914, Monteux led the world premieres of Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun and Jeux, Stravinsky’s Petrouchka and Rite of Spring and Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloë, all cornerstones of twentieth-century ballet. Nearly a half century after moving on to a variegated career, Monteux cut this set with his favorite orchestra of the time, but the result is far from a mere feat of longevity and his age (87) never shows. While tempos tend to be somewhat more deliberate than usual, the aura is only slightly autumnal, as each selection is infused with vitality and warmth, a tangible expression of the deep feeling of humanity Monteux inspired in both colleagues and audiences, which the orchestra reciprocates with gorgeous playing. Perhaps as a sign of respect for them, rather than importing a marquee outside superstar the violin solos are played – beautifully – by the London Symphony concertmaster (Hugh Maguire).

Vitya Vronsky and Victor Babin – (1947)

The orchestral score of Swan Lake was not published until the 1895 revival. Before that, the only available printed version was an 1877 arrangement for piano solo by Nikolay Kashkin, a critic, self-taught musician, fellow teacher and colleague of the composer. (A young Debussy made a fascinating four-hand piano arrangement of #s 20a, 21 and 22 in 1881 that, especially in the Russian Dance, effectively combines his own esthetic with the vastly different one of the composer. A second piano version of the full ballet and a duo-piano version of the suite, both by Eduard Langer, were issued in 1900.) The Russian-born American couple of Vronsky and Babin cut Babin’s own transcription for two pianos of the Act I waltz (# 2) in 1947 on a double-sided 78 included in an album of Tchaikovsky waltzes (and they rerecorded it in stereo in 1960). Far from a straight-forward transcription, Babin begins with a lyrical development of the famous “swan theme,” states the waltz calmly and then takes off with a passionate outburst and riveting vigor (abounding in superb coordination with Vronsky), a deeply personal approach that a full ensemble could never emulate for its sheer agility and extreme liberties. While solo adaptations of the score tend to emphasize classical refinement, the greater density of the doubled resources of the duo-piano versions allows for more overt drama, although any keyboard version sacrifices the suppleness and variety of Tchaikovsky’s engaging instrumentation for a rather thick and monotonous (and unavoidably percussive) sonority.

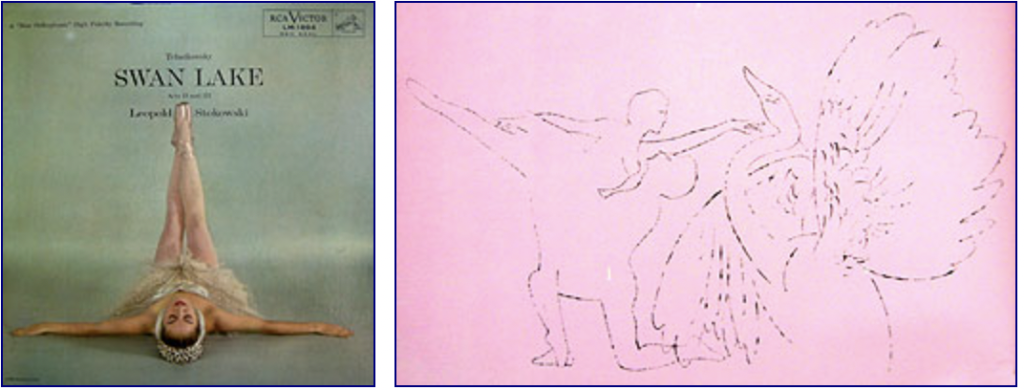

Leopold Stokowski, NBC Symphony Orchestra (RCA, 1955)

Stokowski makes no pretense of deferring to the demands of ballet and unabashedly treats the score as abstract emotion, constantly stretching the tempos for maximum impassioned inflection, spotlighting his soloists and swelling dynamics to define phrases. By doing so, he both illustrates the early criticism of the score and confirms the brilliance of Tchaikovsky’s conception, which works quite well on its own, even when subjected to interpretive extremes. Rather than cherry-pick favorite highlights or adhere to the standard Jurgenson suite, he recalls early productions of only portions of the ballet by presenting just Acts II and III largely intact, but ordering the numbers according to the Langer piano reduction (i.e., omitting the Act III pas de six (# 19), substituting the Act I pas de deux and re-ordering the parts of the Dances of the Swans (# 13)). He also interpolates before the pas de deux coda a polka, presumed to be by Drigo, which is absent from both the Langer and Jurgenson scores. (Stokowski favored a comparable approach to Sleeping Beauty, from which he recorded Aurora’s Wedding, Diaghilev’s reduction mostly of Act III, both in 1953 and in one of his final recordings in 1976 – with huge vitality at age 94!) Finally, the original album (RCA LM-1894) has added visual interest, as its insert of photos and an informative essay is graced with six drawings by a young, unknown New York commercial artist named Andy Warhol. Alas, they were produced with his blotted line technique and were barely visible (and hard to reproduce, although I’ve tried with one). After a half-century, this magnificent recording finally moved beyond vinyl on a Cala CD. Also available is Stokowski’s more moderate and less compelling 23-minute 1964 Decca/London Phase Four set of selections (comprising #s 0, 2, 4c, 5, 10, 11, 21, 27 and 29) with the New Philharmonia, coupled with their Sleeping Beauty suite.

Full Recordings

The arrival of LPs paved the way for recordings of the complete ballet. Yet the various editions, adaptations and “improvements” imposed upon the score throughout its history have challenged the notion of a definitive “complete” version. While timings generally can be useful to indicate relative tempo, those given here reflect the extent to which the full score has been trimmed from its length of about 130 minutes. I’ve focused on the pioneers that led the way to the abundance of current choices.

Frantisek Skvor, Prague National Theatre Orchestra

This appears to be the first recording of Swan Lake claiming to be complete (at least on the front cover – the interior notes, record labels and spine on the Parliament gatefold reissue (PLP 212) all specify “Suite”). Strangely enough, it lies somewhere in between, nearly intact until Act III, omitting only an Act II scene (# 10), but then skipping #s 15, 16 and 17, adding two pieces I couldn’t identify after the Spanish dance (# 21) and then bypassing some of the most memorable portions by jumping from the violin andante of the Act III pas de deux to the final scenes of Act IV (#s 28 and 29). Interestingly, WERM indicates that it was also issued as a set of 14 78s – so might the Parliament LP reissue (the only edition I have) abridge the 78s, as its 87 minutes of music hardly would have required 28 sides?

Barely mentioned in reference works, Skvor was the conductor of the National Theatre in Prague from 1927 to 1960 and was primarily known as a composer of film music. Why he ventured into this bold pioneering project, which appears to be his only extant recording, is unclear. Yet in terms of sheer performance it comes across rather well – no especially distinctive touches but an altogether decent, moderate and respectful rendering that effectively conveys the essence of each number, although careless balances occasionally obscure the glorious melodies beneath their accompaniment. Most gratifying are the quieter passages that are graced with a welcome degree of plasticity, while most of the more vivid sections come across as rather stodgy. The fidelity, though, tends to be blurry and indistinct at low volume, but metallic violins, trumpets and cymbals burst into prominence in the louder portions – possibly a sign of overly-aggressive efforts at noise reduction during processing or transfers, or perhaps an artifact of the original engineering.

An intriguing, if short-lived, mystery of sorts: The 1953 Second Supplement to the authoritative WERM lists not only the Skvor 78s but a separate set of two LPs on the American Urania label, also by the Prague National Theater Orchestra but conducted by Jaroslav Krombholc who, according to the scant available information, apparently was at the Prague Theater at the time, albeit as a specialist in his native Czech opera. As unlikely as it would seem, could there have been a second pioneering performance from the same source? Actually, no. A seasoned collector kindly provided a copy of the Krombholc album which turns out to be the same performance with better balanced fidelity and augmented by an additional 10 minutes of music (perhaps from the 78s?). The most likely explanation seems to be that Urania licensed its releases from Europe but was notorious for changing the names of the artists, presumably in an attempt to avoid liability for royalty fees, and that the editors of the massive WERM compilation understandably had little choice but to accept information provided by distributors, and could not have been expected to discover and weed out duplicates. In any event, the 1957 WERM Third Supplement lists only the Skvor (on LP).

Even more obscure is a c. 1954 Melodiya set with the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra led by Yuri Fayer, who apparently headed the Bolshoi Ballet for a remarkable 40 years and was closely associated with Prokofiev; I haven’t heard it, but I assume that it’s similar to their soundtrack to a crudely-edited 1957 film of a heavily-truncated Bolshoi Swan Lake performance, in which the playing is brash and inflated, ranging from acutely fleet for sections of athletic prowess to hard-driven underlining for sections of drama, with little lyricism in between. The movie serves to raise an intriguing issue as to whether the music accompanying a ballet performance needs to keep a relatively steady pulse and moderate tempos in order to accommodate the dancers, particularly in an ensemble, as I had always assumed, or whether seemingly impulsive shifts are appropriate, especially when the dancers benefit from ample rehearsals and know what to expect, even if the audience is apt to be taken by surprise. Here, the tempos are set by an extremely experienced conductor and his ballet company has no trouble following his seemingly quirky lead. That, in turn, would admit as valid in the context of ballet a significantly wide scope of interpretation, rather than adhering to a more limited range of restraint that I, for one, had presumed to be proper, if not required, as the expected custom for ballet accompaniment.

The Fayer/Bolshoi movie raises a further intriguing question – whether in fact a quintessentially Russian style can be said to exist for this music. Of course, esthetic evolution and the influx of foreign influences (and, especially in Russia, politics) during the intervening generations had created a rather wide gulf between Tchaikovsky’s own time and extant recordings; that, alone, necessarily compromises their historical authenticity. Moreover, a reliable attempt at generalization is defied by a sampling of complete Swan Lake recordings by Russian orchestras led by Russian conductors, as compiled by the Tchaikovsky Research Site – i.e, Juraitis/Bolshoi, 1976; Fedoseyev/Moscow, 1985; Svetlanov/USSR, 1987; Fedotov/Mariiansky, 1994; Yablonsky/Russian State, 2001; Gergiev/Mariiansky, 2006; Pletnev/Russian National, 2010; and Temirkanov/St. Petersburg, 2011 – all of which, remarkably, are on Spotify). Even so, while far from uniform, through varying degrees and combinations of bold tempos, brash textures and rhythmic emphasis they do tend to underline the drama to a somewhat greater extent than their Western counterparts.

Anatole Fistoulari, London Symphony Orchestra – (Decca/London)

Music history abounds with prodigies who reveal their ability on piano, violin and even composition at an amazingly early age, and brilliant young soloists who later turn to conducting, but Fistoulari may have displayed unique talent, reportedly leading Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetique” Symphony in Kiev at age 7. Primarily remembered for concerto accompaniment and ballet (he worked with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the Royal Ballet), his Swan Lake is said to document the version danced at Covent Garden. Running only 91 minutes, it essentially follows the Langer piano score (reordering the Act II swan dances and replacing the Act III pas de six with the Act I pas de deux) but omits #s 3b, 9, 22, 25, 26 and 28 while adding Drigo’s brief polka to the Act III national dances and two of the orchestrated piano pieces to what little is left of Act IV (where the sweet tenderness of the “Valse bluette” and the vigor of the new mazurka seem misplaced within the otherwise pervasive tragic tone, although the mazurka’s pensive end leads smoothly into the finale). Fistoulari achieves a fine balance, subtly underlining the drama of the music while respecting its flow and continuity, including well-sculpted phrases that breathe naturally. Decca’s famed “Full Frequency Range Recording” captures a full (albeit to modern ears somewhat exaggerated) range from room-shaking bass to glossy highs and a wide dynamic range that lets a solo violin frailly whisper rather than overriding its accompaniment. Reportedly, the solos were first recorded with the London Symphony’s first violinist, who so displeased the producer that his sections were recut with Alfredo Campoli, whose renowned sweet tone is amply evident in the release.

In 1961 Fistoulari returned to the studio with Decca, this time to lead a 45-minute set of exerpts with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw (#s 0, 1, 2, 8, 10, 11, 13d, 13e, 20, 5b, 24, 27 and 29). Widely acclaimed and often reissued, it boasts a sense of gracefulness, rhythmic heft and drama beyond the complete London Symphony set. The recording is rich and detailed, with overly-prominent high winds as the only peculiar aspect. The ensemble playing is superb and boiling tympani add a special dash of excitement to climaxes. In 1973 Fistoulari cut yet a third Swan Lake for Decca, this time for its Phase Four imprint with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic and Ruggerio Ricci as the violin soloist. Perhaps as a measure of its relative lack of esteem, nearly alone among stereo Swan Lakes it remained stranded on vinyl for most of the CD era and only appeared as part of a massive 41-disc “Phase Four Stereo Concert Series” box in 2014. A Gramophone review by Ivan Marsh (of the 1991 Dutoit/Montreal set) credited its “passionately Russian impulse” while chiding the “artificially balanced Phase Four recording.” It sought to be absolutely complete by including the two numbers the composer added for the first Moscow performances along with the Drigo pieces.

Antal Dorati, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra (Mercury, 1954)

In addition to his ballet pedigree, already noted, Dorati had a wide-flung career in Dallas, England, Stockholm, Washington and Detroit, but his longest tenure was a decade with the Minneapolis (later renamed Minnesota) Symphony Orchestra, which ended in 1960. Despite its seemingly provincial name, the orchestra already had an illustrious history, as Dorati succeeded Ormandy and Mitropoulos at its helm. Although he recorded most often during the 1950s with the London Symphony, Dorati used “his” orchestra for this recording that, in a liner note, he proudly hailed as “the first time ever” the entire score “as Tchaikovsky wrote it and intended it to be performed” was presented “unaltered, either for the stage or for concert purposes.” For once the claim of a complete recording seems merited, as it does follow the full orchestral score as published by Jurgenson, including all 29 numbers while omitting the two added vanity sections, the Drigo polka and the orchestrated piano pieces. (Beyond his devoted service to Haydn, Dorati was the first conductor to record complete versions of all three Tchaikovsky ballets; he also recut The Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty in stereo with the Concertgebouw for Philips.) Perhaps unsure of the commercial appeal of the whole set, Mercury issued the Dorati/Minneapolis recording both as a deluxe 3-LP box and on three separate albums of Acts 1, 2/4 and 3.

Along with Paul Paray and his Detroit Symphony, Dorati was the featured conductor for the independent Mercury label. Prior to stereo, its Living Presence technique eschewed multiple inputs and mixing by using a single microphone hung about 15 feet behind the podium with the orchestra in its standard concert configuration on the stage of an auditorium in order to achieve, as the album proclaimed, a “completely natural balance among the instrumental choirs and between featured solo instruments and orchestra.” Although without stereo directionality for added aural realism, heard today it still impresses mightily, and without any trickery in digital remastering – to preserve the original sound, the Mercury CD was supervised by Wilma Cozart, who had produced the original recording and whose husband Robert Fine was the technical supervisor and engineer. Dorati’s rhythms are hugely invigorating – the opening scene (# 1) fairly leaps out of the groove (or digital track) and the following waltz challenges anyone to sit still. Perhaps to show their mettle compared to their better-known competition, his Minneapolis forces play with world-class caliber and the solos proudly display their concertmaster, Rafael Druian, in a consistently compelling and utterly timeless recording.

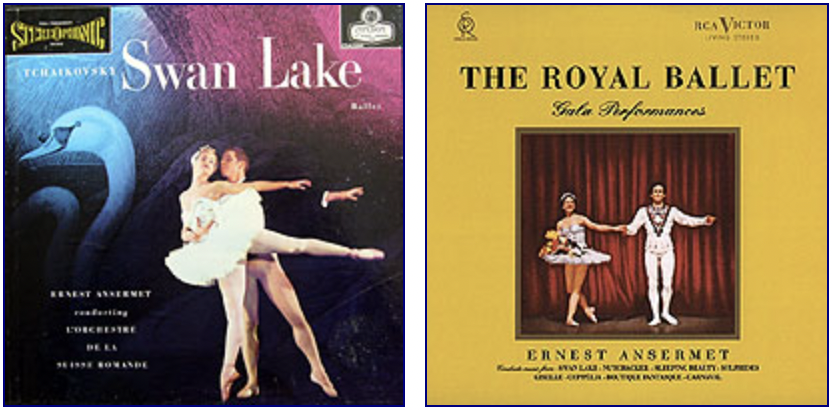

Ernest Ansermet, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande (Decca/London)

Ansermet, too, had a solid background as conductor of the Ballets Russes for eight years, succeeding Monteux and leading premieres of key works by Satie, Prokofiev and especially Stravinsky. Devoted to his native Switzerland, he founded the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande in 1918 and served as its principal conductor for a half-century (although he did guest-conduct other ensembles). In keeping with his earlier career in mathematics, he became known for clarity, balance, rhythmic steadiness and moderated transitions, all of which seem ideally suited to ballet. Yet while the execution and recording are exceptional, and even though the result is far from mechanical, this first stereo set seems largely unengaged and drained of emotion – a serviceable introduction to the score, perhaps, and a suitable accompaniment for performance, yet missing the special touches of other audio presentations. Ansermet basically follows the orchestral score, but with substantial omissions (#s 3, 6, 9, 14, 16, 19, and 24-27). That same year, leading the Covent Garden Orchestra, Ansermet included four excerpts (#s 10, 13d, 13e and 2) in The Royal Ballet – Gala Performances, a deluxe album in the RCA Soria series which has attained legendary status, commanding astounding prices on the collectors’ market but for reasons barely related to the performances, which share the same basic restrained, patient disposition as the Suisse Romande set, albeit with marginally greater suppleness and outstanding fidelity.

Maurice Abravanel, Utah Symphony (Vanguard, 1967)

As Dorati did for Mercury, Abravanel legitimized Vanguard, another independent pop label seeking a foothold in the classical market, garnering great respect and attention for his extensive series of recordings, especially of Mahler, with the Utah Symphony which he developed from a part-time community group to world-class status and led for 32 years. (As a token of its gratitude, the orchestra named its concert hall after him.) But their Swan Lake should be valued for reasons well beyond documentation of their professional achievement, which was already amply evident from a superb set of Swan Lake highlights that they had cut for Westminster a decade earlier (comprising #s 10, 13c, 13e, 13d, 13b, 13f, 2, 15, 20, 21, 5a, 5d and 29) which in comparison is slightly less polished but with a bit more vigor and crisper sonics. For the full recording Abravanel takes the somewhat expected cuts of the narrative sections: #s 3, 6, 9, 14, 16, 19, 25 and 26. While a few tempos tend to vary from the norm they remain fully convincing, and the full recording is enlivened by incisive fidelity, capped by penetrating cymbals (which can tend to get a bit wearisome). While it really doesn’t matter much now, the original Vanguard album wins the prize for the blandest cover of all Swan Lakes – while a provocative photo might be cheating, surely the whole point of a cover is to do more than merely state the contents in block lettering, and this one looked more like a bootleg than an invitation to savor the extraordinary work of art that lay within.

Following the eight-year gap between the Ansermet and Abravanel albums the floodgates opened, with a new Swan Lake set issued every other year or so. Many boost their claim of being complete by including not only all the numbers in the orchestral score that we’ve used as a guide, but all of the added materials as well –the Russian Dance and the Act III pas de deux for Siegfried and the Black Swan, both of which Tchaikovsky wrote and inserted during the original Moscow run, plus the three “interpolations” that Drigo orchestrated from Tchaikovsky piano pieces and the polka that he presumably wrote himself, all of which swell the total time to over 2½ hours and, except for the Russian Dance, sound less inspired and can seem to bloat rather than enhance the overall experience. Of the more recent sets, the 1991 Decca album with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra led by Charles Dutoit (with violin solos played by Chantal Juillet, his future wife) seems to have garnered the widest critical acclaim. Even though its smooth execution rarely hits the toe-tapping flair of some others, it’s gorgeously played and recorded and to my ears (and eyes – what an exquisite cover!) largely succeeds in conveying the full range of emotion with which Tchaikovsky imbued his fabulous score. Completists should note, though, that it omits the Drigo material – no major loss – as well as the Act II finale (# 14, a 2½ minute repetition of the “swan theme”) thus ending Act II with the upbeat coda to the dances of the swans (# 13f). While presumably done to fit the first two acts onto a single 78-minute CD, this provides an emotionally satisfying, if dramatically dubious, conclusion to the first disc. Yet despite its splendor this set only supplements, rather than supplants, my esteem and affection for the pioneering recordings that dared to lead the way for all that would follow.

Resources

As usual, I’ll take full credit and blame for the musical judgments while gratefully acknowledging the following sources for the information and quotes used in this article:

- Anderson, Zoë: The Ballet Lover’s Companion (Yale, 2015)

- Balanchine, George and Francis Maron: Balanchine’s Complete Stories of the Great Ballets (Doubleday, 1954)

- Clough, Francis and G. J. Cuming: The World’s Encyclopedia of Recorded Music (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1950), plus Supplements I (1951), II (1953) and III (1957)

- Cochrane, Peggy: notes to “The Art of the Prima Ballerina” LP set (London CSA 2213, 1959)

- Demidov, Alexander P.: “Swan Lake,” entry in Selma Jean Cohen, ed.: International Encyclopedia of Dance (Oxford, 1998)

- Goodwin, Noël: “The Classical Ballet in Russia to 1900,” article in Stanley Sadie and John Tyrell, eds.: The New Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2001 edition (Oxford, 2001)

- Greshovic, Robert: Ballet 101 (Hyperion, 1998)

- Gruen, John: The World’s Greatest Ballets (Abrams, 1981)

- Kaufman, Sarah: Dance Review (Washington Post, January 27, 2017)

- Kirsten, Lincoln: “Ballet Music,” article in Elie Siegmeister, ed.: Music Lover’s Handbook (William Morrow, 1943)

- Lee, Carol: Ballet in Western Culture: A History of its Origins and Evolution (Allyn & Bacon, 2002)

- Leonard, Alfred: notes to Desormiere/French National LP (Capitol CTL 7015, 1951)

- Lerman, Leo: “The Art of Swan Lake,” essay in the Ormandy/Philadelphia LP (Columbia KS 6308, 1962)

- Lyons, James: notes to the Stokowski/New Philharmonia LP (London Phase Four SPC 21008, 1964)

- Martin, John: “Swan Lake – The Ballerina’s Ballet,” essay in the Stokowski/NBC Symphony LP (RCA LM 1894, 1955)

- Nugent, Ann: Swan Lake – Stories of the Ballet (Barrons, 1985)

- Reid, Charles: notes to the Irving/Philharmonia LP (EMI CLP 1018, 1953)

- Scholes, Percy: “Ballet,” entry in Oxford Companion to Music, 9th edition (Oxford, 1955)

- Schonberg, Harold: Lives of the Great Composers (3d edition, Norton, 1997)

- Terry, Walter: “The History of Swan Lake,” essay in the Dorati/Minneapolis LP set (Mercury OL3-102, 1954)

- Tubeuf, André: notes to Désormière LP reissue (EMI References 2C 051-86029)

- Williamson, Michael: notes to the Ansermet/Suisse Romande LP set (London CSA 2204, 1959)

And finally, some unconventional but indispensable (and free!) on-line resources: (But please note that I do not use or condone sites offering unlicensed downloads of currently-available commercial material. Such sites are not only illegal but unethical, as they steal well-deserved income from artists and legitimate distributors and thus undermine the financial incentive to continue their valuable work.)

- The full orchestral and piano scores, along with the supplementary numbers, are all available from the fabulous Petrucci Music Library.

- As part of an extensive website devoted to Tchaikovsky, the Tchaikovsky Research Site, a “collaboration of Tchaikovsky scholars and enthusiasts worldwide,” includes a set of remarkably informative pages that focus on Swan Lake, including lists of editions, biographies of major personages and a fairly thorough discography.

- YouTube and Spotify (among others) have utterly transformed my approach by providing access to most of the recordings I’ve mentioned, together with many more. When I began this site I had to depend upon my own collection and whatever I could find in local libraries. Then, I expanded my resources by buying additional CDs and LPs though eBay and Amazon. Now, nearly everything I might want to hear is online. Amazing!! What could possibly come next?